Accepting compliments

Have you ever been in a situation where you know you’ve done a good job, been told as much, but found you instantly brush that compliment under the carpet?

Are you told: ‘you’re special,’ ‘you mean a lot to me,’ ‘you’re important,’ but none of these quite manage to sit well for you- something inside you stops you absorbing that compliment and making it your own… sound familiar?

What’s going on in that moment?

I’m going to tackle it from my modality- Person Centred Counselling:

In our interactions with people, from the minute we are born we listen and try hard to live up to what is expected of us, it can mostly be said that what we learn daily when we are growing up allows us to fit in, socialise and complete tasks for survival in order to function in our families, friend groups and society. Great- we have some good tools to get going and live our lives. We are told these rules by parents, siblings, family members, teachers, government etc and in order to fit in we mostly follow these rules to a greater or lesser extent; they help us form our opinions on our values, morals and ethical outlook on the way we live and how others live their lives.

So, where did these rules come from originally: learned experience, family history, world history, observations and religious teachings to name but a few. Somebody imparting expectations on to you from their own frame of reference is called an Introject– it’s placed upon for you to follow and it becomes ingrained in your thought patterns and outward behaviours, you may pass these on to other people too but originally they did not belong to you; they usually include the word ‘should.’

When introjects become really embedded in our routines then they can become a Condition of Worth: the success or failure of carrying out an internalised expectation affects how you feel about yourself; which inevitability affects your self-esteem and identity.

How do these play out in reality and what do they have to do with compliments?

Introject from parents: ‘We’ll only be proud of you if you become a doctor, you should become a doctor, why are you doing history at college?’

Teenager: No interest in medicine; is particularly happy outdoors in nature and likes history.

Introject from parents: ‘A doctor’s title carries respect and stability; you should become a doctor; history won’t get you anywhere’

Teenager: Respects most career choices and is confused as to why there is status attached to a role that they don’t wish to pursue, and why is the respect of their parents attached to it too?

Introject from parents: ‘You won’t amount to anything worthwhile if you don’t become a doctor, you should listen to us, we know best.’

Teenager: Has heard this so many times they start to believe that there is only one option to satisfy their parents and their own feelings of worthiness. Sees a job advertised for English Heritage as a tour guide but feels like they won’t get the job so what is the point in applying.

Lecturer: ‘Great essay last week on the Norman invasion! – You made some strong points and you really know your stuff.’

Teenager: Feels they need to try harder, a good grade wasn’t enough, but also feels what’s the point because their parents won’t let them pursue this, doesn’t believe the lecturer and feels it is false hope being spread to them. Doesn’t tell parents about their good grade. Has felt sad and frustrated for a number of weeks.

The example demonstrates how if you hear the same negative things repeatedly is can become something that you start to judge yourself against. It wasn’t your thought to start off with, it’s connected to influential people in your life and you want to please them, but it feels like it’s going against the grain of what you as a person want to do. It can often cause anxiety symptoms because you feel threatened in some way, either by the situation or by not meeting expectations. The teenager’s ambition here is in complete contrast to their parents, the implied message here from them is: ‘if you don’t become what we want you to be then we’ll effectively love you less.’ The introject is being used here as a manipulation and it has become a condition of worth for the child- the teenager can’t accept their achievements nor the compliment they receive because they aren’t inline with the original expectations that have been levied at them. They feel ‘less than’ and so anything that follows will be viewed negatively and used as evidence to reinforce that they aren’t worthy of love, support or praise and that they must try harder.

If your opinions are very bound up in those close to you, then it is important to question where have the opinions come from and who do they serve?

If you find you have an inner critic analysing your every move and holding you accountable against other people’s expectations, then it is OK to question:

- Whose voice is saying this to me?

- Is it in line with my goals for me or someone else’s goals for me?

- What have I been told repeatedly about myself that isn’t truly what I think about me?

- What’s the evidence that I am a failure?

- What evidence is there that I’m working towards my own goals?

- If I removed the external expectations of me, what am I left with that belongs to me?

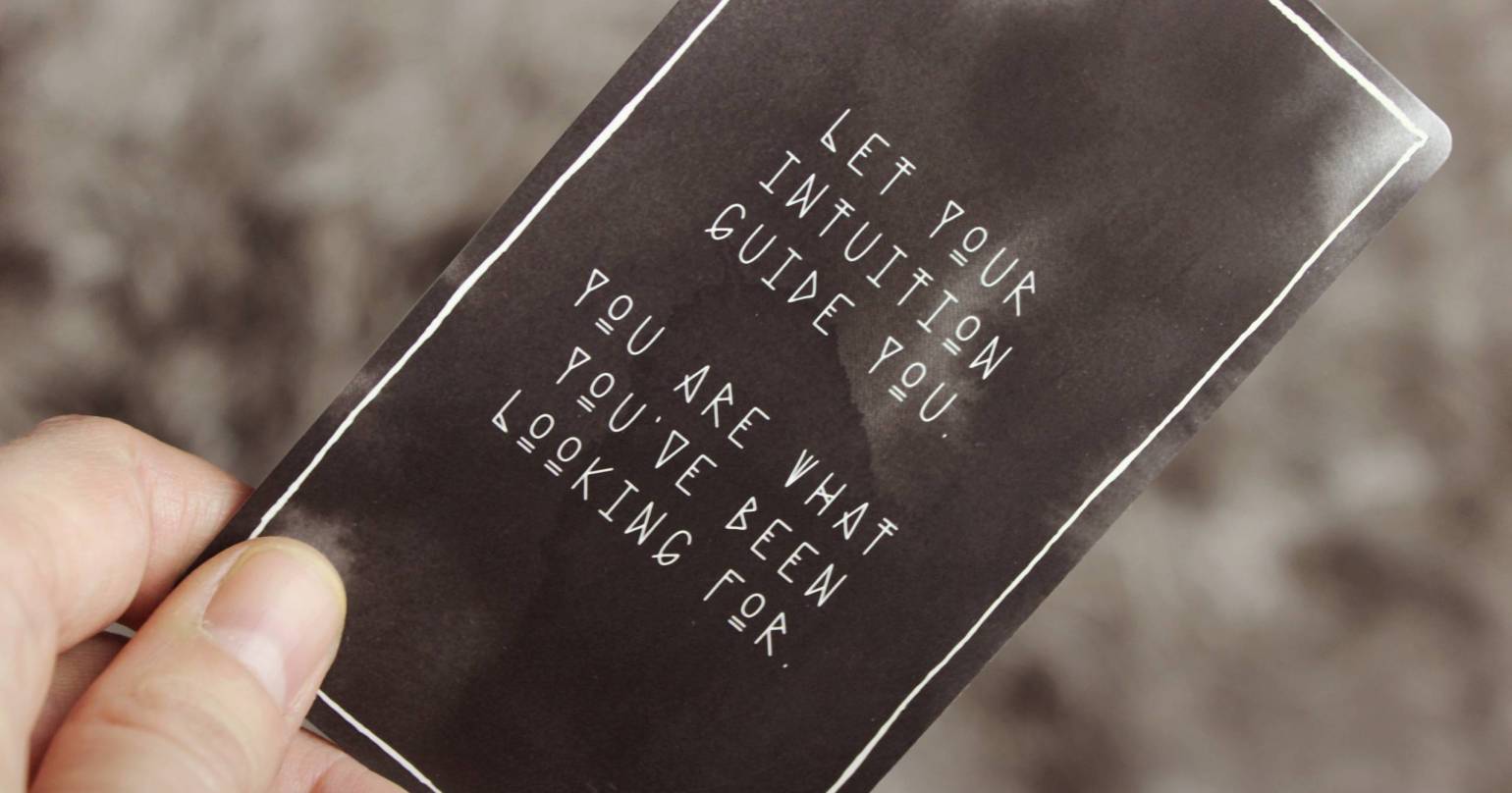

Essentially, we can’t accept compliments if we don’t believe we are worthy of them, if we aren’t connected to the effort and determination we endured to get to where we are today, and if the people around us aren’t supportive and encouraging of OUR goals. The more you can question the ownership of your negative thoughts then the more you can peel back the layers to find your true and original self; not the self that is operating to please others. If you can engage with the real-self then you can start to appreciate your own worth, independent of other people’s opinions of you.

Add Comment